OpenAI’s Code Red

OpenAI’s Code Red Is a Reminder That First Mover Advantage Is Fragile

When Sam Altman declared a company-wide “code red” at OpenAI earlier this month, it was striking not because of the urgency, but because of what it implicitly conceded. The company that sparked the consumer gen AI boom is now on the defensive. ChatGPT still dominates consumer mindshare, but OpenAI is being forced to refocus on fundamentals as competitors close the gap, surpass benchmarks, and win where it may matter most: enterprise adoption and distribution.

Code red moments usually arrive when a company realizes that momentum has shifted. OpenAI’s internal memo made clear that the immediate priority is improving ChatGPT’s day-to-day experience, not launching new moonshots. Speed, reliability, personalization, and breadth of answers are existential priorities rather than incremental improvements. That framing alone suggests that OpenAI no longer believes technical leadership is enough to carry the business forward.

The Myth of the Permanent First Mover

The popular narrative around OpenAI has been that it “won” early and would compound from there. History rarely works that way in platform technology. First movers create markets, but they rarely monopolize them. The advantage erodes quickly once competitors catch up on core functionality and then differentiate on distribution, trust, and integration.

ChatGPT’s launch was a shock to the system. It forced Google, Microsoft, and the broader tech ecosystem to accelerate timelines that were admittedly already in motion. But three years later, foundation models are no longer scarce, and the gap between frontier and fast follower has narrowed to quarters, not years.

Google’s Comeback Shows How Distribution Wins Late

Google’s resurgence is the clearest example of why first mover advantage fades. Gemini’s latest releases have outperformed OpenAI models on several industry benchmarks, but benchmarks alone are not the real story. Google’s real advantage is that it thinks less about “selling” Gemini. It can “distribute” it through mature, existing channels.

By embedding Gemini directly into search, Workspace, Android, and Chrome, Google turns its existing surfaces into an on-ramp for AI usage. Monthly active users reportedly climbed from roughly 450 million to 650 million in a matter of months, driven not by viral adoption but by channel placement. This is classic platform economics. Distribution reduces friction, lowers customer acquisition costs, and accelerates iteration through scale.

OpenAI, by contrast, must convince users to seek out ChatGPT as a destination. That distinction matters far more than marginal model quality differences once performance converges.

Anthropic’s Enterprise Success

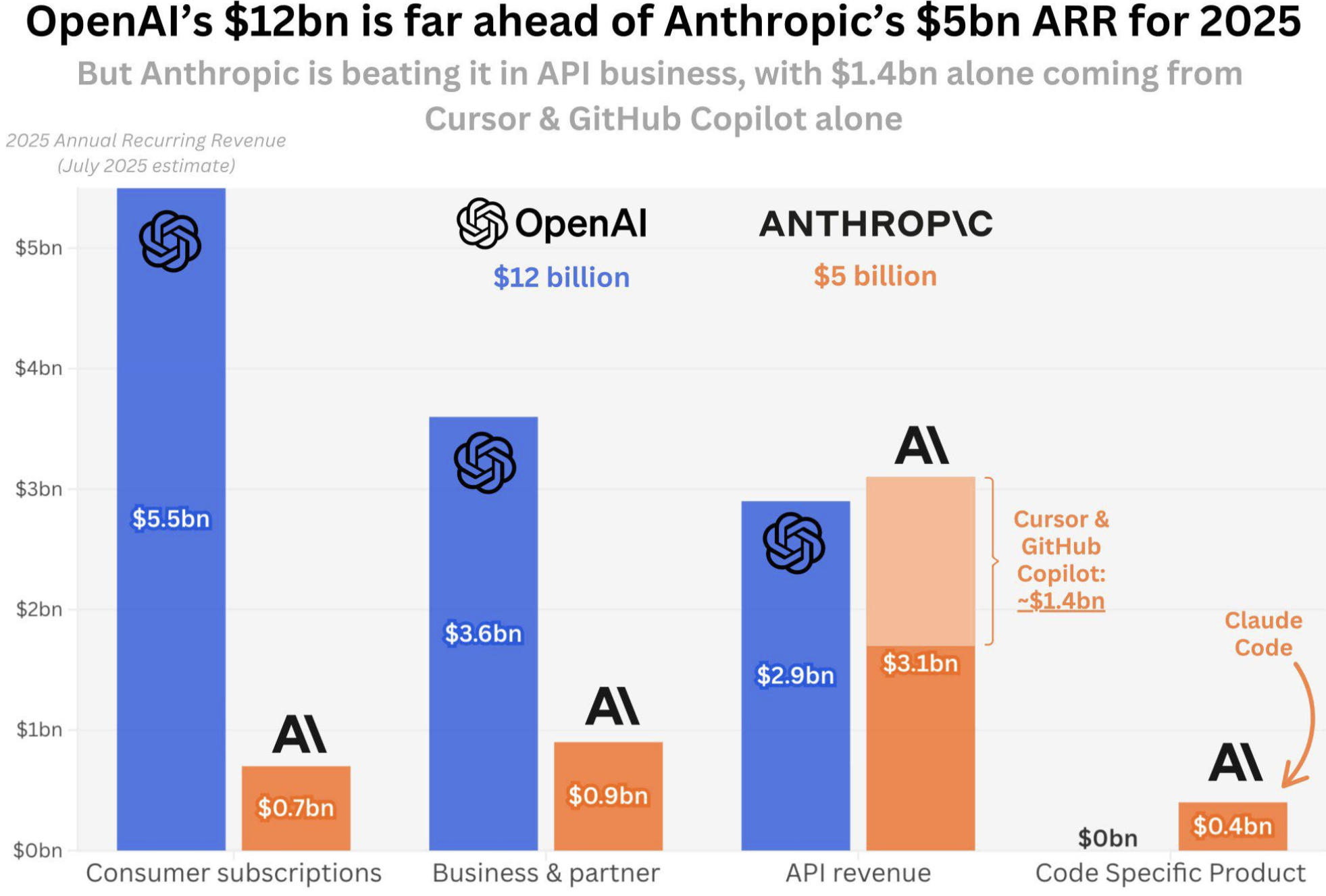

If Google demonstrates the power of consumer distribution, Anthropic highlights where OpenAI is most exposed: the enterprise. Claude has steadily gained share among enterprise users, developers, and regulated industries, not because it is flashier, but because it is predictable, controllable, and easier to operationalize.

Enterprise buyers care less about novelty and more about reliability, safety, and integration into existing workflows. Anthropic’s focus on clearer refusal behavior and enterprise-friendly deployment has resonated with buyers who are wary of hallucinations and reputational risk. While ChatGPT dominates headlines, Claude is increasingly embedded behind the scenes.

This divergence matters because enterprise revenue is where long-term value accrues. Consumer subscriptions are meaningful, but historically only a small fraction of freemium users ever convert. Enterprise contracts are stickier, higher margin, and more defensible. Losing momentum there is far more dangerous than losing Twitter discourse.

Source: The information reporting (https://www.theinformation.com/)

Peter Gostev (https://www.linkedin.com/in/peter-gostev/)

OpenAI’s Strategic Diffusion Problem

One of the most telling elements of the code red memo was not what OpenAI accelerated, but arguably what it delayed. Advertising initiatives, shopping agents, healthcare tools, and a personal assistant called Pulse were all deprioritized. OpenAI has attempted to pursue multiple identities at once: consumer app, enterprise platform, model provider, and experimental product lab. That breadth made sense when capital was abundant and technical leadership was unquestioned. It becomes a liability once competitors match capability and force tradeoffs.

Google’s early history offers a useful contrast. Its relentless focus on search created a compounding advantage that made later adjacencies inevitable. OpenAI’s diffusion has arguably diluted focus at the exact moment when competitors were converging on its core strengths.

Model Differentiation Is No Longer a Moat

A second implication of code red is that OpenAI no longer believes sustained model differentiation is guaranteed. This is not an indictment of its research talent - it is more a recognition of structural reality. As capital, talent, and compute flood into the ecosystem, performance gaps shrink.

Even subjective differentiation, such as tone and personality, has proven difficult to stabilize. OpenAI’s models have notoriously gone between being overly agreeable and overly sterile, reflecting the challenge of serving both consumer engagement and enterprise utility with a single core system. That tension is easier to manage when you own the distribution channel and customer context. It is harder when your product must be everything to everyone.

Once models commoditize, the winner is determined by where they are embedded, not how they score on benchmarks.

The Nvidia Signal and the Capital Question

Another underappreciated signal is coming from the capital markets. Nvidia recently disclosed that there is no guarantee it will finalize a previously announced long-term agreement with OpenAI, despite headline numbers suggesting up to $100 billion of investment over time. The distinction between an announcement and a contract matters.

OpenAI is committing to hundreds of billions in future data center and compute investments. The question investors are now asking is not whether AI demand exists, but whether OpenAI can convert that demand into predictable, high-margin revenue fast enough. Enterprise traction and distribution leverage directly affect that answer.

When partners, suppliers, and markets start scrutinizing timelines and unit economics, urgency inside the company is inevitable.

Consumer AI Is a Distribution Game, Not a Feature Race

For consumer products, code red underscores a hard truth. The battle is no longer about who builds the smartest chatbot. It is about who controls the surfaces where AI becomes a habit.

Google’s search box, Apple’s operating systems, and Microsoft’s productivity suite are default distribution channels. OpenAI does not own an equivalent surface. ChatGPT must be intentionally opened, subscribed to, and remembered. Improving personalization and speed helps retention, but it does not solve distribution asymmetry.

This is why OpenAI’s consumer lead feels more fragile than it appears. Without structural distribution, consumer loyalty is shallow and easily disrupted by defaults.

The Takeaway for Founders and Investors

The lesson from OpenAI’s code red is not that the company is failing. It remains one of the most important and valuable AI companies in the world. The lesson is that first mover advantage is fleeting when underlying technology diffuses quickly.

Anthropic and Google are winning meaningful ground not by being first, but by being better positioned. Enterprise share is shifting toward reliability and trust. Consumer share is shifting toward embedded distribution. Neither outcome is driven primarily by raw model performance.

For founders, this is a reminder to treat early momentum as a wedge, not a moat. For investors, it is a reminder that sustainable advantage in AI will accrue to those who control workflows, defaults, and budgets, not just benchmarks.